Finding the Prophet in His People

Finding the Prophet in His People by Ingrid Mattson

I spent a lot of time looking at art the year before I became a Muslim. Completing a degree in Philosophy and Fine Arts, I sat for hours in darkened classrooms where my professors projected pictures of great works of Western art on the wall. I worked in the archives for the Fine Arts department, preparing and cataloging slides. I gathered stacks of thick art history books every time I studied in the university library. I went to art museums in Toronto, Montreal and Chicago. That summer in Paris, "the summer I met Muslims" as I always think of it, I spent a whole day (the free day) each week in the Louvre.

What was I seeking in such an intense engagement with visual art? Perhaps some of the transcendence I felt as a child in the cool darkness of the Catholic Church I loved. In high school, I had lost my natural faith in God, and rarely thought about religion after that. In college, philosophy had brought me from Plato, through Descartes only to end at Existentialism — a barren outcome. At least art was productive — there was a tangible result at the end of the process. But in the end, I found even the strongest reaction to a work of art isolating. Of course I felt some connection to the artist, appreciation for another human perspective. But each time the aesthetic response flared up, then died down. It left no basis for action.

Then I met people who did not construct statues or sensual paintings of gods, great men and beautiful women. Yet they knew about God, they honored their leaders, and they praised the productive work of women. They did not try to depict the causes; they traced the effects.

Soon after I met my husband, he told me about a woman he greatly admired. He spoke of her intelligence, her eloquence and her generosity. This woman, he told me, tutored her many children in traditional and modern learning. With warm approval, he spoke of her frequent arduous trips to refugee camps and orphanages to help relief efforts. With profound respect, he told me of her religious knowledge, which she imparted to other women in regular lectures. And he told me of the meals she had sent to him, when she knew he was too engaged in his work with the refugees to see to his own needs. When I finally met this woman I found that she was covered, head to toe, in traditional Islamic dress. I realized with some amazement that my husband had never seen her. He had never seen her face. Yet he knew her. He knew her by her actions, by the effects she left on other people.

Western civilization has a long tradition of visual representation. No longer needing more from such art than a moment of shared vision with an artist alive or dead, I can appreciate it once more. But popular culture has made representation simultaneously omnipresent and anonymous. We seem to make the mistake of thinking that seeing means knowing, and that the more exposed a person is, the more important they are.

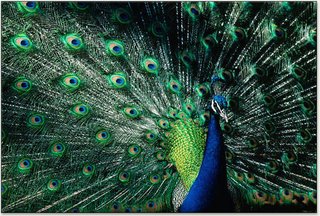

Islamic civilization chose not to embrace visual representation as a significant means of remembering and honoring God and people. Allah is The Hidden, veiled in glorious light from the eyes of any living person. But people of true vision can know God by contemplating the effects of his creative power,

Do they not look to the birds above them,

Spreading their wings and folding them back?

None can uphold them except for The Merciful.

Truly He is watchful over all things (Qur'an, 67:19)

If God transcends his creation, it is beyond the capacity of any human to depict him. Indeed, in Islamic tradition, any attempt to depict God with pictures is an act of blasphemy. Rather, a Muslim evokes God, employing only those words that God has used to describe himself in his revelation. Among these descriptive titles are the so-called "99 Names of God," attributes that are recited melodiously throughout the Muslim world: The Merciful, the Compassionate, the Forbearing, the Forgiving, the Living, the Holy, the Near, the Tender, the Wise…. Written in beautiful script on lamps, walls, and pendants, each of these linguistic signs provokes a profoundly personal, intellectual and spiritual response with each new reading.

Deeply wary of idolatry, early Muslims with few exceptions declined to glorify not only God, but even human beings through visual representation. Historians, accustomed to illustrating accounts of great leaders with their images captured in painting, sculpture and coin have no reliable visual representations of the Prophet Muhammad. What we find, instead, is the Prophet's name, Muhammad, written in curving Arabic letters on those architectural and illustrative spaces where the sacred is invoked. Along with the names of God and verses of the Qur'an, the name Muhammad, read audibly or silently, leads the believer into a reflective state about the divine message and the legacy of this extraordinary, yet profoundly human messenger of God.

Words, written and oral, are the primary medium by which the life of the Prophet and his example have been transmitted across the generations. His biography, the seerah, has been told in verse and prose in many languages. Even more important than this chronological account of the Prophet's life are the thousands of individual reports of his utterances and actions, collected in the hadith literature. These reports were transmitted by early Muslims wishing to pass on Muhammad's tradition and mindful of the Qur'an's words: "Indeed in the Messenger of God you have a good example to follow for one who desires God and the Last Day" (Qur'an, 33:21). Eager to follow his divinely inspired actions, his close companions paid attention not only to his style of worship, but also to all aspects of his comportment — everything from his personal hygiene to his interaction with children and neighbors. The Prophet's way of doing things, his sunnah, has formed the basis for Muslim piety in all societies where Islam spread. The result was that as Muslims young and old, male and female, rich and poor, adopted the Prophet's sunnah as a model for their lives, they became the best visual representations of the Prophet's character and life. In other words, the Muslim who implements the sunnah is an actor on the human stage who internalizes and, without artifice, reenacts the behavior of the Prophet. This performance of the sunnah by living Muslims is the archive of the Prophet's life and a truly sacred art of Muslim culture.

I first realized the profound physical impact of the Prophet's sunnah on generations of Muslims as I sat in the mosque one day, watching my nine year old son pray beside his Qur'an teacher. Ubayda sat straight, still and erect beside the young teacher from Saudi Arabia who, with his gentle manners and beautiful recitation, had earned my son's deep respect and affection. Like the teacher, Ubayda was wearing a loose-fitting white robe that modestly covered his body. Before coming to the mosque, he had taken a shower and rubbed fragrant musk across his head and chin. With each movement of prayer, he glanced over at his teacher, to ensure that his hands and feet were positioned in precisely the same manner. Reflecting on this transformation of my son, who had abandoned as his normal grubbiness and impulsivity for cleanliness and composure, I thought to myself, "thank God he found a good role model to imitate."

In my son's imitation of his teacher, however, it occurred to me that there was a greater significance, for his teacher was also imitating someone. Indeed, this young man was keen in every aspect of his life to follow the sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad. His modest dress was in imitation of the Prophet's physical modesty. His scrupulous cleanliness and love of fragrant oils was modeled after the Prophet's example. At each stage of the ritual prayer he adopted the positions he was convinced originated with the Prophet. He could trace the way he recited the Qur'an back through generations of teachers to the Prophet himself. My son, by imitating his teacher, had now become part of the living legacy of the Prophet Muhammad.

Among Muslims throughout the world, there are many sincere pious men and women; there are also criminals and hypocrites. Some people are deeply affected by religious norms, others are influenced more by culture — whether traditional or popular culture. Some aspects of the Prophet's behavior: his slowness to anger, his abhorrence of oath taking, his gentleness with women, sadly seem to have little affected the dominant culture in some Muslim societies. Other aspects of his behavior, his generosity, his hospitality, his physical modesty, seem to have taken firm root in many Muslim lands. But everywhere that Muslims are found, more often than not they will trace the best aspects of their culture to the example of the Prophet Muhammad. He was, in the words of one of his companions, "the best of all people in behavior."

Living in America, my son's role model might have been an actor, a rap singer or an athlete. We say that children are "impressionable," meaning that it is easy for strong personalities to influence the formation of their identity. We all look for good influences on our children.

It was their excellent behavior that attracted me to the first Muslims I met, poor West African students living on the margins of Paris. They embodied many aspects of the Prophet's sunnah, although I did not know it at the time. What I recognized was that, among their other wonderful qualities, they were the most naturally generous people I had ever known. There was always room for one more person around the platter of rice and beans they shared each day. Over the years, in my travels across the Muslim world, I have witnessed the same eagerness to share, the same deep belief that it is not self-denial, but a blessing to give away a little more to others. The Prophet Muhammad said, "The food of two is enough for three, and the food of three is enough for four." During the recent attacks on Kosovo, there were reports of Albanian Muslims filling their houses with refugees; one man cooked daily for twenty people domiciled in his modest home.

The Prophet Muhammad said, "When you see one who has more, look to one who has less." When I was married in Pakistan, my husband and I, as refugee workers, did not have much money. Returning to the refugee camp a few days after our wedding, the Afghan women eagerly asked to see the many dresses and gold bracelets, rings and necklaces my husband must have presented to me, as is customary throughout the Muslim world. I showed them my simple gold ring and told them we had borrowed a dress for the wedding. The women's faces fell and they looked at me with profound sadness and sympathy. The next week, sitting in a tent in that dusty hot camp, the same women — women who had been driven out of their homes and country, women who had lost their husbands and children, women who had sold their own personal belongings to buy food for their families — presented me with a wedding outfit. Bright blue satin pants stitched with gold embroidery, a red velveteen dress decorated with colorful pom-poms and a matching blue scarf trimmed with what I could only think of as a lampshade fringe. It was the most extraordinary gift I have ever received — not just the outfit, but the lesson in pure empathy that is one of the sweetest fruits of real faith.

An accurate representation of the Prophet is to be found, first and foremost, on the faces and bodies of his sincere followers: in the smile that he called "an act of charity," in the slim build of one who fasts regularly, in the solitary prostrations of the one who prays when all others are asleep. The Prophet's most profound legacy is found in the best behavior of his followers. Look to his people, and you will find the Prophet.